Here's an example of one conundrum from Hauser's study:

"Denise is riding a train when she hears the engineer suddenly shout that the brakes have failed. The driver then faints from the shock. On the track ahead stand five people who are unable to get off the track in time to avoid being hit by the train. Denise sees a sidetrack leading off to the right onto which she can steer the train, but one person stands on that track as well. She can turn the train, killing the one person, or do nothing and allow the five people to be killed instead."

Hauser wanted to know if it was morally permissible for Denise to switch the train to the sidetrack, sacrificing one but saving five.

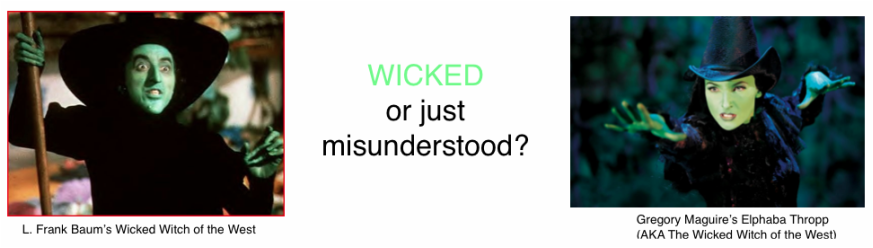

Remember when you were six and your grandma first introduced you to The Wizard of Oz? Even in the movie, you thought that the Wicked Witch of the West was an evil hag who wanted to kill Dorothy. You were convinced at a young age that the witch was evil to the core. Now, skip ahead sixteen to seventeen years later and you encounter Gregory Maguire's Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West. And as you are reading this book you discover that that green witch that you hated in The Wizard of Oz, didn't start off immediately as being evil. In fact, you find out that the Wicked Witch of the West was never evil at all!

Psychology Today by Alex Lickerman, M.D.: http://www.psychologytoday.com/collections/201405/morality-matters/the-truth-about-morality

Maguire, Gregory. Wicked: The Life and times of the Wicked Witch of the West: A Novel. New York: Regan, 1995. Print.

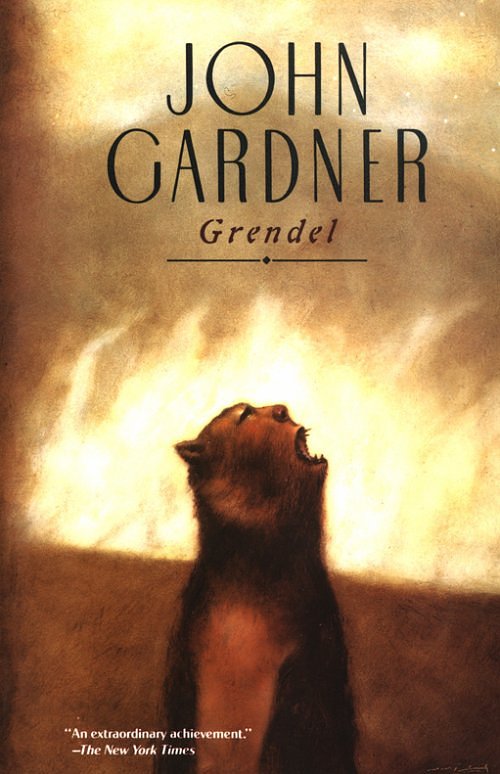

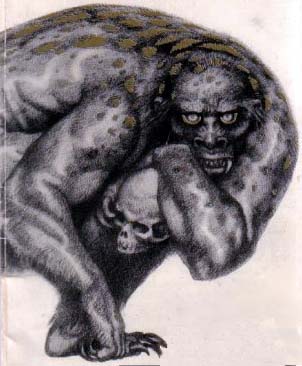

Gardner, John. Grendel. New York: Knopf, 1971. Print.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed